Algorithmic Music OGs

How serialism, quantum music, indeterminacy, and Duchamp are all related.

A few weeks ago, I wrote about the pioneers (OGs) of neural networks for music.

But many of you rightly pointed out that I missed some key names :)

Previous post focused on early scientific papers.

This one turns to artists:

Marcel Duchamp (was he into music?)

Arnold Schoenberg (serialism)

John Cage (indeterminacy)

Karlheinz Stockhausen (total serialism)

Pierre Boulez (total serialism)

Iannis Xenakis (formalized, mathematical)

Laurie Spiegel (interactive)

David Cope (early AI, classical)

Curtis Roads (granular synthesis)

Benoît Carré and François Pachet (early AI, pop)

Eduardo Reck Miranda (early AI, quantum)

Who am I missing?

Marcel Duchamp — Erratum Musical (1913)

Like most of Duchamp’s work, is ANTI-ESTABLISHMENT.

Against all stablished conventions (of music, in this case).

Written for 3 voices, followed those rules:

Duchamp wrote 25 notes on slips of paper.

He shuffled and drew them at random, determining their sequence.

Notes were then assigned to 3 vocal parts.

In this second piece, with the same title, Duchamp again used chance to make music.

Arnold Schoenberg — Suite for Piano, Op. 25 (1923)

This piece is SERIALISM in its essence (using the twelve-tone technique):

He organized all 12 notes of the chromatic scale into a tone row (or series).

The row must use all 12 pitches without repetition before any pitch can be reused.

The row can be manipulated in four main ways:

Prime (original form)

Retrograde (reversed order)

Inversion (intervals flipped)

Retrograde inversion (reversed inversion)

These forms can also be transposed to start on any pitch.

John Cage – Music of Changes (1951)

He pioneered INDETERMINACY in music.

Where some elements of a piece are not determined and left to chance.

In this piece, chance is resolved using the I Ching (a Chinese text).

Karlheinz Stockhausen — Kontra-Punkte (1953)

Stockhausen and Boulez (below) were key figures in TOTAL SERIALISM.

TOTAL SERIALISM orders musical elements like pitch, rhythm, and dynamics using a serialized system.

Remember that SERIALISM (by Schoenberg) focused only on pitch.

Pierre Boulez — Le Marteau sans maître (1955)

This is also TOTAL SERIALISM.

System-controlled music that still sounds unpredictable and fragmented.

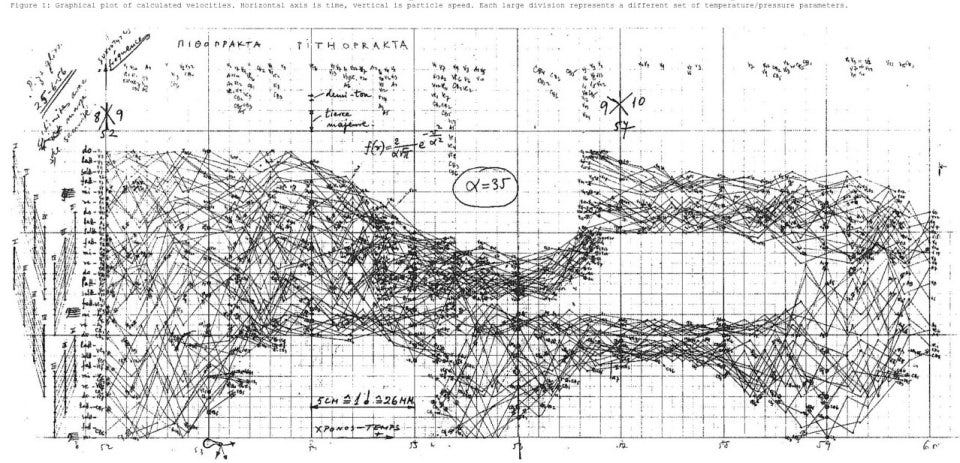

Iannis Xenakis – Pithoprakta (1956)

Pithoprakta means "actions through probability".

It is composed based on the statistical mechanics of gases.

Xenakis also published “Formalized Music: Thought and Mathematics in Composition”, a very influential book.

Laurie Spiegel – Music Mouse (1986)

She pioneered INTERACTIVE algorithmic composition on early computers and synthesizers.

Her vision, in her words:

One of the big changes is that music is becoming a process that people can participate in – rather than a bunch of fixed, finite entities called pieces that you can listen to that are the same every time.

David Cope – Experiments in Musical Intelligence (1980s)

His EARLY AI project analyzes composers’ works to generate new pieces in their style.

Computer compositions were in the style of Bach, Mozart, or Beethoven.

Curtis Roads — Microsound (2001)

He popularized GRANULAR SYNTHESIS through his compositions and book “Microsound” (2001).

GRANULAR SYNTHESIS is a sound synthesis method that creates complex textures by combining tiny sound particles (grains).

It sounds like this.

Benoît Carré and François Pachet — Hello World (2019)

This is a good example of AI-based music before deep learning.

Contemporary AI POP, based on Markov models.

François Pachet also co-authored the book “Deep Learning Techniques for Music Generation”.

Eduardo Reck Miranda — AI and quantum

He is a composer-scientist who uses AI and QUANTUM computing to make music.

His contributions also include books:

The first piece is AI-assisted.

The second is QUANTUM music.

QUANTUM computers use quantum bits (qubits), which can exist in multiple states at once.

Disclaimer. The views expressed are my own and do not reflect the opinions or positions of my employer.

Amazing! Great Read!